Many high school students are now choosing their courses for the coming year.

The choices students make in grades 10 and 11 will have a significant impact on their lives after graduation. But students, families — and even educators — have little information about the outcomes associated with different course types.

Our research drew on data from 10 cohorts of Toronto District School Board students to track their progress for five years from the start of Grade 9.

We found a strong association between students completing at least one Grade 12 “U” (university) course by the end of high school and applying for any post-secondary education (not only university, but also college). We also found differences across race and disability in terms of which students are taking “U” courses and which aren’t.

These findings are especially important for students, families and guidance counsellors at this time of year as youth are choosing courses.

Post-secondary education matters

Officially, in our K-12 education system, success is defined as simply having a high school diploma.

This limited definition is despite overwhelming evidence suggesting those who proceed to post-secondary education live longer and healthier lives.

They also earn more, are more civically engaged and are more likely to report that they are flourishing — surely, outcomes we all care about.

But as our report details, the Ministry of Education characterizes students’ post-secondary goals as “personal” and their post-secondary pathways as individual choices.

This individualistic framing negates the significant group-based inequities in post-secondary education access among high school graduates.

Group-based differences in access

Our study, I Have All My Credits, Now What? examined data from 156,580 students. The students started Grade 9 between 2006-15.

We found that the difference between the percentage of East Asian students going to post-secondary study (86 per cent) and the percentage of Latin American students going (50 per cent) was almost 36 per cent. This difference far exceeds the 19 per cent gap in graduation rates between the same groups.

Similarly, relatively few students who self-identify as Black or Mixed when asked about their race go on to post-secondary education (55 and 61 per cent, respectively).

Group-based differences are even greater for students with disabilities, measured by formal or informal identification through special education.

The patterns in this data needs to be understood not as merely reflecting individual “choices.” Instead, the focus on group-based differences in who accesses post-secondary should be understood as disparities in access. These access disparities raise questions about the system itself.

A key factor driving divergent post-secondary outcomes are the type of academic courses (English, math, science, geography, history, and so on) in which students enroll.

Significance of Grade 12 ‘U’ courses

In the next weeks, the vast majority of students will choose between either University (“U”) and College (“C”) courses in grades 11 and 12.

In theory, both types of courses leave the doors open for post-secondary access.

But most people are unaware of data showing that all university-bound students, and two-thirds of college-bound students, complete at least one Grade 12 “U” course by the end of high school.

Our study found that among the quarter of graduates with no Grade 12 “U” courses, 71 per cent did not apply to post-secondary education at all. Only 23 per cent made the transition to college.

We also showed that U-level English and math courses are particularly important “gatekeeping” courses. Students from groups who are less likely to go on to post-secondary education are less likely to take the “U” courses that expand opportunities.

Preventable systemic discrimination

These discrepancies point to preventable systemic discrimination —especially because group-based differences in “U” course enrollment persist after we control for achievement.

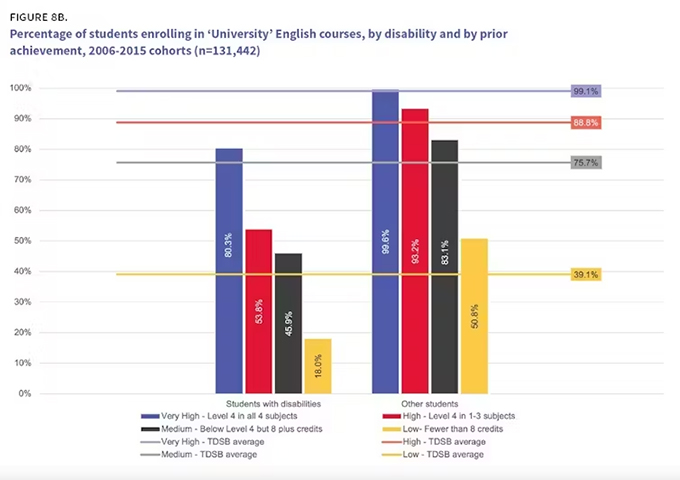

Let’s take the example of disabled students: Among non-disabled students, virtually every student who got all As in their academic subjects in Grade 9 enrolled in Grade 12 U-level English (99.6 per cent).

Percentage of high school students enrolling in English courses labelled ‘U’, by disability and prior achievement. (Kelly McKay), Author provided (no reuse)

But among the students with disability who had the same marks, only 80 per cent took the course that is so important for accessing post-secondary education.

For students with fairly high (they obtained one to three As in Grade 9) or medium achievement the differences are even greater. A large majority of non-disabled students who got all their credits but no As in Grade 9 enrolled in Grade 12 U-level English (83 per cent). Among disabled students with comparable marks, only 46 per cent took the gateway course.

Key life decisions

It is critical that students and families making key life decisions know about the very uneven long-term outcomes of choosing between these misleadingly labelled “U” and “C” upper-year courses: As our research showed, “U” courses are in fact not only critical for pathways to university, they are also associated with pathways to college. We need to see systemic change to disrupt these patterns.

Our research suggests that the premise underpinning the provincial government’s “many pathways to success” is flawed.

Even with the dearth of public reporting on post-secondary education and equity outcomes, there are clear — but poorly understood — disparities.

And these differences create pathways to lifetime inequalities in health, earnings and happiness for marginalized youth — and a less inclusive and prosperous society.

Author Bios: Kelly Gallagher-Mackay is Assistant Professor of Law and Society at Wilfrid Laurier University, Carl E. James is Professor, Jean Augustine is Chair in Education, Community & Diaspora at York University, Canada, Christine Corso is a PhD Candidate in Educational Leadership and Policy at the University of Toronto, Gillian Parekh is Canada Research Chair (Tier 2) in Inclusion, Disability and Education and Robert S. Brown is an Adjunct Professor, Faculty of Education and in Critical Disability Studies both at York University, Canada